When screens replace conversations living parents wondering how to get their kids back.

The Gen Z and mostly kids are known for their technology adiction and disorder behaviour.

Growing up Online, Struggling Offline

From Roblox binges to constant scrolling, today’s children are more connected than ever — yet drifting further from the real world.

Ali’s World

It’s nearly 9 p.m. and Ali is still glued to his phone, deep in a Roblox mission. His mother calls him for dinner. No response. A second call, louder this time. “I’m busy!” he snaps. The game isn't over — and neither is his screen time. He’s been playing since he got home from school.

Ali is not an exception. He is the norm.

Like thousands of children across the UK, Ali’s daily life revolves around a screen — from the moment he wakes up, to bedtime arguments over device limits. His world is vivid, fast-moving, and endlessly scrollable. But away from his screen, Ali is withdrawn, easily irritated, and uncomfortable in social settings.

A Day in Ali’s Life

A glimps’into Ali's journey & and he spend his time!

Journey Started

School Preparation

Going to school

After School

Activities

Continuous Screen

Engagement

Bedtime

Sleeping

The impact isn’t just about lost time!

Ali’s story is far from unique. Around the world, millions of children are following a daily routine just like his — glued to screens, increasingly disconnected from the people around them.

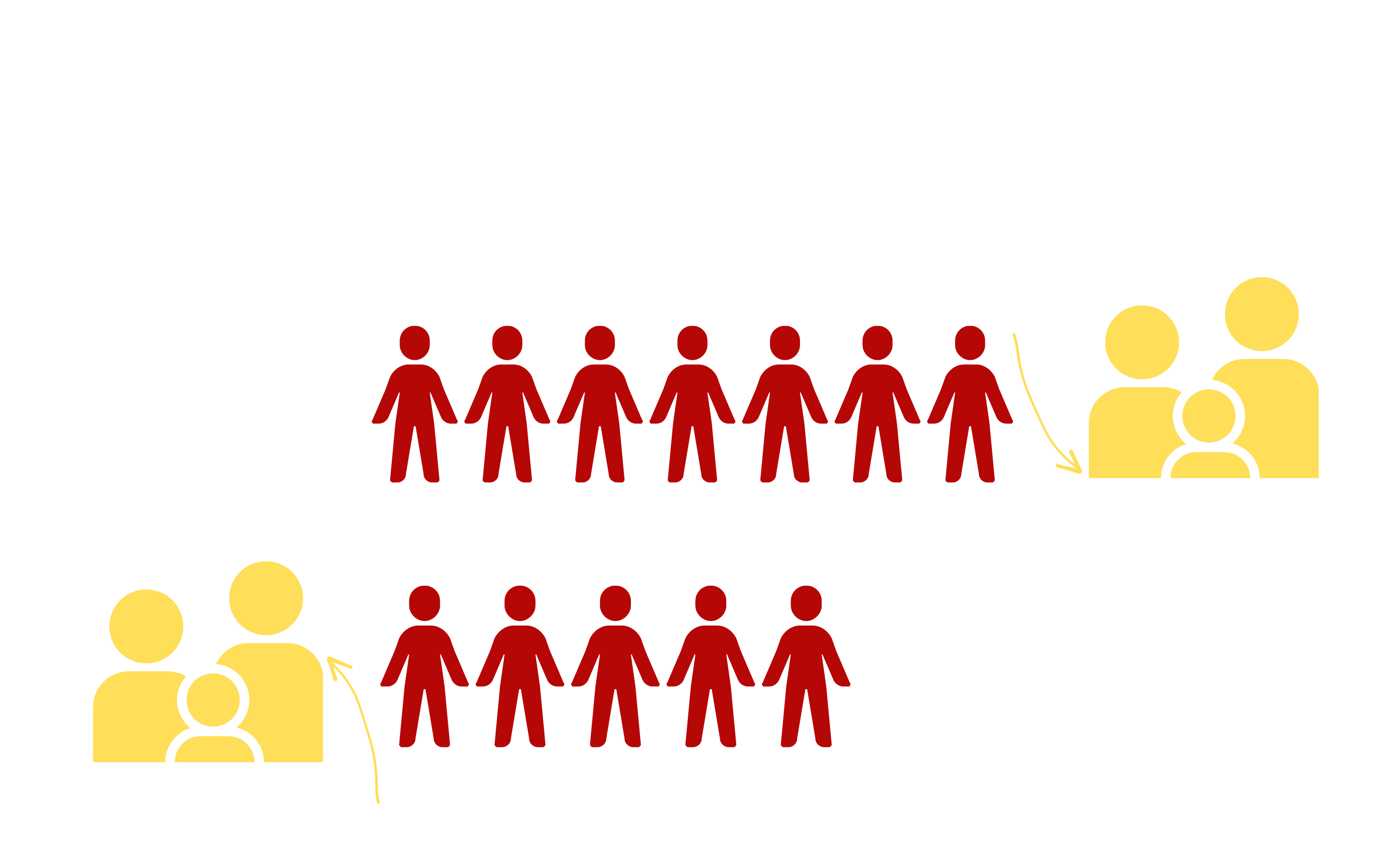

In the UK, this trend starts alarmingly young. According to Ofcom’s Children and Parents: Media Use and Attitudes Report 2024,nearly a quarter of children aged 5 to 7 already own a smartphone — and 38% are using social media platforms like YouTube and TikTok, despite minimum age restrictions.

These early habits quickly become entrenched. British children aged 3 to 17 now spend an average of 4 hours and 36 minutes daily on screens for entertainment — not including schoolwork. Much like Ali, many spend their evenings locked into online games, social media feeds, and short-form videos that leave little space for real-world connection.

Globally, the pattern is strikingly similar. UNICEF estimates that one in three internet users worldwide is a child, many of whom are navigating this space alone, without consistent guidance or safeguards.

In the United States, a 2023 study by Common Sense Media reported that tweens (ages 8–12) now spend over 5.5 hours daily on screens, while teens (13–18) spend almost 9 hours a day, excluding homework.

Like Ali, many of these children are overstimulated online and disengaged offline. The impact isn’t just about lost time — it’s about a generation struggling to build confidence, focus, and real-life connections in an overwhelmingly digital world

— A Mother’s Quiet Grief:

Saba, mother of 15-year-old Ali and 9-year-old Hania, speaks with a quiet heaviness — the kind that comes from watching her children drift into digital worlds she can no longer reach.

“Ali never enjoys sitting with us during meals anymore,” she says. “He doesn’t clean his room, and doesn't want to go out with us. He’s just lost interest in me.”

Once, bedtime was their moment — when Ali would curl up beside her and recount every little detail of his day before finally heading to his bed. “Now his games, his laptop, and mobile phone have replaced me,” she says. “He doesn’t talk anymore — he just scrolls or plays.”

Although Ali is still doing well in school, his teachers often complain that he seems distracted. “Even though he’s bright, he zones out. He finds it hard to focus — unless it's a game or a video.”

The digital world has also blurred Ali’s confidence. “He can’t even decide if he wants braces. He can’t pick what to wear. But he takes online challenges and wins. He’s bold behind a screen, but unsure of himself in real life.”

But it’s not just Ali. Saba’s worry has doubled with her younger daughter, Hania. “She’s only nine, and already spends hours on Roblox and watching YouTube Shorts,” she says. “She gets annoyed when I ask her to stop. And now, she and Ali don’t even talk to each other much. They just sit in the same room, lost in different screens.”

Saba’s voice breaks as she reflects: “Sometimes, I feel like I’ve lost both of them — not to something bad, but to something I can’t compete with.”

In homes like Saba’s, the struggle is not about screen time limits alone. It’s about something deeper — the slow unraveling of connection, routine, and emotional closeness in a world where digital companions are always available, always demanding attention.

“It’s Like They’re Together, but Alone”

Amar, an experienced English teacher and curriculum manager, has witnessed the digital transformation of teen life from the frontlines of education. Over the past few years, he’s noticed a striking shift in how young people interact — not just with their devices, but with each other.

“There’s a stronger tendency toward online interaction, even when they’re physically together,” he explains. “Group chats, memes, and short-form video culture have replaced a lot of real conversations — even during break time.”

In the classroom, Amar sees the effects firsthand. Students are more distracted and less engaged, particularly when lessons require sustained attention or deeper thinking.

The digital world has also blurred Ali’s confidence. “He can’t even decide if he wants braces. He can’t pick what to wear. But he takes online challenges and wins. He’s bold behind a screen, but unsure of himself in real life.”

“Phones are a constant low-level distraction,” he says. “Even when they’re not actively using them, just having a phone nearby seems to tug at their attention.”

He’s had to adapt his teaching style to keep students focused: breaking tasks into smaller chunks, adding interactive elements, and building in frequent check-ins. Still, the long-term changes in behaviour are hard to ignore.

During breaks, many students prefer scrolling in silence over chatting with friends. “I’ve noticed some kids actually feel more at ease online than face-to-face. It creates a social barrier — they’re side by side, but not really together.”

Confidence has taken a hit too. Public speaking and group work, once routine parts of school life, have become anxiety-inducing for many. “They hesitate to share ideas, avoid eye contact, mumble, or completely shut down under pressure,”

Amar says: “Some prefer voice notes or texts because they fear real-time judgment.”

While educators like Amar observe the immediate behavioral shifts in students, psychologists are delving into the deeper, long-term mental health implications of excessive screen use among adolescents.

From smartphones and tablets to social media and gaming platforms, today's children are growing up in a world of constant digital stimulation and diminishing real-world interaction. A 2019 report by the UK Chief Medical Officers noted correlations — though not causation — between screen time and mental health issues. However, the mounting evidence, including accounts from child psychologists and protection officers, paints a troubling picture: children’s emotional development is being fundamentally altered by life online.

Children today are immersed in a digital world that shapes their minds far beyond screen time alone. From cyberbullying and explicit content to toxic beauty standards, they’re exposed to harmful material long before they’re emotionally equipped to process it. Studies show this exposure distorts their sense of self, fuels anxiety, and contributes to rising rates of harmful behavior and mental health issues. The danger lies not just in how long they’re online — but in what they’re absorbing while they’re there.

Screens aren’t just tools — they are shaping the emotional architecture of an entire generation

“We’re not just talking about too much screen time — we’re talking about how devices are rewiring how children feel, relate, and respond… Emotional comfort now lives in a device — not in a parent’s hug, not in a conversation, not in real human contact… That’s what we mean by emotional architecture — their feelings are being framed by screens.”— Rakia Raza, Child Psychologis

What was once distraction is now displacement. Children are learning to soothe, celebrate, and suffer through screens — and parents are struggling to catch up.

As children grow older, managing their screen use becomes increasingly challenging for parents and teachers. What begins as casual digital interaction in early childhood often transforms into deep emotional dependence during adolescence. Many parents feel overwhelmed by the pace and complexity of the digital world — content is faster, more immersive, and often beyond their understanding. Teachers echo this concern, observing that taking away a phone from a student can feel like stripping away their sense of safety. The growing gap isn’t just about screen time; it’s about losing influence to a digital world that feels more real to children than the one around them.

Ali, a 15-year-old boy, gives us a window into this new reality. “It’s not like I just sit and play one game all day,” he says. “I like being in my room, playing guitar, watching videos, or chatting with friends online. I spend about 8 to 10 hours there because I don’t have cousins or extended family around — there’s no one to hang out with in person. So, the screen becomes my space.”

For Ali, digital life is more than entertainment — it fills a gap that family or community once might have. “Sometimes I do feel alone,” he admits, “but when I’m watching streams or talking to friends, it feels like I’m not really by myself. That’s where I feel most at ease.” His experience shows that screens are no longer simply tools or toys — they’ve become emotional lifelines, offering comfort, connection, and a sense of belonging that can be hard to find offline.

Ali’s story highlights a wider issue: the emotional needs of young people are increasingly being met through screens, while parents and educators struggle to catch up. This disconnect is not just about technology — it’s about a shift in how children relate to the world, and who or what they turn to when they need support.

Why Games Are So Addictive

Ali’s obsession with Roblox isn't accidental—it's by design. Modern digital games are meticulously crafted to engage players deeply, leveraging psychological principles that tap into the brain's reward system.

At the core of this engagement is dopamine, a neurotransmitter associated with pleasure and reward. When players achieve in-game goals—like completing a level or unlocking a new feature—the brain releases dopamine, reinforcing the behaviour and encouraging repetition.

These games often employ variable reward schedules, where rewards are given unpredictably. This unpredictability heightens engagement, as players are motivated to continue playing in anticipation of the next reward. This mechanism is akin to the principles observed in operant conditioning studies, where variable rewards can lead to persistent behaviour.

Furthermore, the "compulsion loop" is a design strategy used in many games. It involves a cycle of anticipation, activity, and reward, creating a loop that players find hard to break. This loop keeps players engaged, often leading them to spend extended periods in the game environment.

Recognizing the potential for such patterns to lead to problematic behaviour, the World Health Organization (WHO) has classified "Gaming Disorder" in its 11th Revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11). This classification describes a pattern of gaming behaviour characterized by impaired control over gaming, increasing priority given to gaming over other activities, and continuation of gaming despite negative consequences.

For parents like Saba, these insights shed light on the challenges they face. What may seem like harmless entertainment is, in many cases, a complex interplay of psychological triggers designed to maximize engagement, often at the expense of real-world interactions and responsibilities.

Global Responses: What Governments Are Doing

Governments around the world are waking up to the silent epidemic of screen addiction among young people — and they are beginning to respond, some with urgency, others with caution.

In France, a 2018 law banned mobile phone use in primary and middle schools, aimed at "disconnecting children from screens and reconnecting them with reality".

China has taken some of the most stringent measures globally. In 2021, it imposed national gaming curfews for minors, limiting online games to one hour on Fridays, weekends, and holidays. Chinese platforms like Douyin (TikTok's sister app) have a "youth mode" that limits time and restricts content.

South Korea has launched government-backed digital detox camps and partnered with health ministries to detect and treat screen addiction in youth.

Denmark's "Screen-Free Schools" initiative is gaining traction, encouraging schools to go tech-light during the academic day. Some municipalities offer resources for parents to co-create digital boundaries with children at home.

In India, the Ministry of Education issued Digital Wellbeing Guidelines in 2022, encouraging schools to implement balanced screen policies and educate families about safe digital practices. However, widespread enforcement remains a challenge given the country’s digital divide.

Across Africa, where mobile penetration is rapidly expanding, countries like Kenya and Rwanda are working with NGOs and tech companies to introduce digital literacy into the national curriculum. Rwanda’s "Digital Ambassadors" programme targets rural areas with screen-awareness campaigns and parent training workshops.

The United States has no federal policy on children’s screen time, but states are acting independently. Utah, for instance, passed a 2023 law requiring parental consent for minors to use social media and setting curfews for teen use. The U.S. Surgeon General also issued a public health advisory warning of social media’s risks to mental health.

Meanwhile, the UK has issued non-binding guidance for schools and families, leaving many educators and parents calling for more defined national policy. With Ofcom data showing that 97% of children aged 12-15 own smartphones, the question is no longer whether screens shape childhood, but how much longer we can afford to ignore it.

What Ali really thinks about

"It's not like that—I continuously play one game. Usually I like to be in my room playing guitar, watching videos or chatting with friends. I usually spend 8 to 10 hours a day in my room... because I don't have cousins or extended family here. I like to stay behind a screen.

I can connect with friends and dive into games or videos. It's my way of hanging out since I don't have family nearby.

Sometimes I feel isolated, but streaming and chatting keeps me company—it’s my comfort zone."

Finding Balance at Home

Ali, Hania, and the First Steps Back in Ali's living room, the Wi-Fi is still on, but something has shifted. After months of quiet struggle, Saba decided to try a different approach. Instead of snatching devices away or arguing about screen time, she called a family meeting. They sat — awkwardly at first — and made three simple promises: more shared meals, one tech-free evening per week, and a new tradition — a weekend walk where no one brings a phone.

The change didn’t happen overnight. Ali still plays Roblox. Hania still sneaks YouTube Shorts when she thinks no one is watching. But slowly, the temperature in the house began to shift. They talked a little more. Ali cooked with his mum once. Hania started drawing again.

“I realised I didn’t want to win a war over screen time,” Saba says. “I just wanted my kids to look up — even if just for a moment.”

Bridging the Gap: From Global Stats to Everyday Choices

While global figures paint a powerful picture of a generation growing up online, real change begins in living rooms like Ali and Hania’s. Behind the data are everyday families trying to reconnect. The following guide offers practical steps parents can take — not to eliminate screens, but to restore balance, build trust, and reclaim moments of presence in an always-connected world.